William Ernst Ehrich Biography

by Nancy Ehrich Martin, Archivist, University of Rochester

and Roger W. Ehrich, Professor Emeritus, Virginia Tech

| Abstract | Kurzfassung | Аннотация |

Introduction

In the upstate New York communities of Buffalo and Rochester are found numerous works of sculpture, bas reliefs, ceramics, plaques and other works of public art created by William Ernst Ehrich. Few are recognized as the work of this remarkable man who immigrated from Eastern Europe to this country on the eve of the Great Depression, bringing with him the artistic visions and skills of a German expressionist tradition founded by sculptors who preceded him like Barlach, Lehmbruck, and Kolbe. To know the man and his background is to add content to the art. This biography connects this Western New York artist to the works many of us see daily, thereby enhancing our understanding of both.To help in understanding the artist's early history and to locate his birth place of Königsberg, East Prussia geographically, several maps are helpful:

- Prussia, 1866, showing Prussia in the German Confederation (Deutscher Bund) just before the Austro-Prussian War,

- Europe, 1911, showing Germany (Deutsches Reich) before World War 1,

- Samland, 1931, showing German village names, and

- Samland today, showing an area of about 45 × 51 km.

The Old World

William Ernst Ehrich was born on July 12, 1897 in the Hanseatic city of

Königsberg [now

Kaliningrad] in what was then the political entity of East Prussia. He was the

oldest son and second of the eight children of Friedrich Wilhelm Ehrich and his

wife Henriette Bader. His oldest sister, Anna, lived but a year and a half,

dying before he was born, leaving him the eldest of his parents' subsequent seven

children [three brothers: Walter, Friedrich and Kurt; and three sisters:

Charlotte, Helene and Friedel.] Of these siblings, Friedrich (Fritz), the

youngest, died of blood poisoning as a boy of six years of age in 1916.

William Ernst Ehrich was born on July 12, 1897 in the Hanseatic city of

Königsberg [now

Kaliningrad] in what was then the political entity of East Prussia. He was the

oldest son and second of the eight children of Friedrich Wilhelm Ehrich and his

wife Henriette Bader. His oldest sister, Anna, lived but a year and a half,

dying before he was born, leaving him the eldest of his parents' subsequent seven

children [three brothers: Walter, Friedrich and Kurt; and three sisters:

Charlotte, Helene and Friedel.] Of these siblings, Friedrich (Fritz), the

youngest, died of blood poisoning as a boy of six years of age in 1916.The Ehrich family was from Kreis Mohrungen, a rural area in the northwest corner of the Mazurian Lakes, now Poland, southwest of the city of Königsberg. It appears that the family had lived in this area since at least the early 18th century and were farmers and tradesmen. William Ehrich's father, Friedrich Wilhelm Ehrich, was born in Groß Sauerken as one of six children (five sons, one infant daughter died). One of Friedrich's brothers, Karl Ehrich, uncle of William Ehrich, was to play a role in the artist's future even though he emigrated to the United States in 1898.

At some point Friedrich Wilhelm Ehrich left Mohrungen and established his family in the city of Königsberg. Although trained as a stone mason, he became Ofenmeister, supervisor in a heating plant in the Kosse district where gas was extracted from coal. The family lived on the north side of the city at Beydritter Weg 9, which was a 12-family apartment building. Other extended family members lived here as well. According to William Ehrich's sister Friedel, the family was "healthy, hard working, directed, agreeable and happy."

According to Friedel, the family was "more poor than rich. Rich in children." The father's income was minimal. In spite of this, the family managed to take vacations to visit those family members who still lived in the country, such as Uncle August, who farmed near Klein Simnau on the Rothlof See. They also frequented the Baltic coast regions to the north with its cliffs, forests, beaches and endless white sand dunes.

A major influence on this family was the Methodist church to which they belonged. They were very active, participating in youth groups, Sunday school, choir and worship. Major events in the family such as baptisms and confirmations were all celebrated within the church. The musical activities involved all of the children. William learned to play the violin and mandolin.

William Ehrich describes his boyhood and early art education (American Artist, 1946):

"To begin with, it might be of some interest that I was born at the tail end of the last (19th) century when Impressionism was flourishing. As a small boy I liked to whittle, and early I went to art classes doing ship carving - supplying my parents, relatives and friends with towel boards and boxes. When the time arrived for the decision concerning a career, my choice was to become a sculptor-carver. I was given in the care of an old woodcarver as an apprentice, and attended an art school part time. Nothing particular happened then until I began to attend classes full time. Though I received scholarships I was a bad art student. In life class, I did not pay enough attention to detail - made my instructor complain that I never would make the grade as an artist. In lettering I had my own ways, neglected too much the German gothic, and from the sculpture class I often took my compositions and carvings home to preserve some of the good points that were in them."

It is important to note that William was a scholarship student. The family did not have sufficient resources to provide higher or specialized education for the children. Nevertheless, each of the surviving children learned a profession. Two of William's brothers, Walter and Kurt became accomplished architects, practicing in the Rhineland after WWII.

At the age of 16 William entered the State Art School in Königsberg, the Staatliche Kunst- und Gewerkschule. The program he entered was rigorous, and the students' work was held to a very high and exacting standard. He would continue as a student in this school until the mid 20s, with an extensive interruption caused by World War I.

The artistic legacy of Königsberg was formalized in 1842 after Prussian president Theodor von Schön convinced Friedrich Wilhelm IV to permit the establishment of an art academy in a new building in the Königstraße. Von Schön and art historian Ernst August Hagen, professor at the Albertina, were the driving forces in bringing to reality the artistic life and future of the city. In 1881 Johann Friedrich Reusch came to Königsberg and established a sculpture class at the Art Academy, thus founding the "Königsberg sculpture school". In spite of the wartime losses of public art in Königsberg, many pieces survive. Among them is the work of the artists who would become the teachers of William Ehrich.

William studied initially under the famous artist Hermann Brachert (1890-1972) and later also under Erich Schmidt-Kestner (1877-1941), and Franz Andreas Threyne (1888-1965) from whom he probably acquired his skills as a ceramist. After 1926 William himself executed numerous works in architectural sculpture under Schmidt-Kestner, Threyne, and Stanislaus Cauer (1867-1943) of the Kunst Akademie (art academy). Today, despite the immense destruction of cultural artifacts in the Königsberg region during WWII, some of their work survives. Efforts continue to locate looted art work, to reconstruct major work that was lost, and to restore damaged work that has been recovered. A year before his death William worked with Heinrich Kirchner (1902-1984) in Munich to study wax and sandcasting.

Much of Brachert's work has survived, and there is a small museum in his former home in Georgenswalde (now Otradnoje) near the Baltic resort of Rauschen where it can be seen. Brachert refused to endorse national socialism and in 1933 lost his job and the ability to exhibit. As a result, his work was removed from public view, which aided the survival of many pieces. His former home is now a tourist destination near Rauschen, which received minimal damage during the war. Two principal pieces are the bronze Nymphe located on the promenade in Rauschen, and Wasserträgerin (girl with water pitcher). These large pieces are similar in concept to Ehrich's work.

Erich Schmidt-Kestner was Director of Sculpture at the Kunst- und Gewerkschule in Königsberg for only 8 years and only a few of his sculptures there survive. Some of his best known sculptures were animals located on the grounds of the Königsberg Zoo. The bronze Zwei spielende Windhunde (two playing greyhounds) from the entrance to the zoo were recently rediscovered and are now in the city art gallery, and a bronze bust of Ernst Wiechert is now in the Museum Stadt Königsberg in Duisburg.

William Ehrich's education at the Königsberg sculpture school was interrupted by

the maelstrom of the First World War. There was no question of not serving.

Military service was compulsory for all able bodied men aged 17-45. The Soldbuch

(paybook) for Muskateer Willy Ehrich shows that he entered military service

March 3, 1916. The main unit of the German Army was the Infantry Regiment, with

soldiers recruited at the local level. He was assigned to the Infantry Regiment

Herzog Karl von Mecklenburg-Strelitz Nr. 43, 18th Company.

William Ehrich's education at the Königsberg sculpture school was interrupted by

the maelstrom of the First World War. There was no question of not serving.

Military service was compulsory for all able bodied men aged 17-45. The Soldbuch

(paybook) for Muskateer Willy Ehrich shows that he entered military service

March 3, 1916. The main unit of the German Army was the Infantry Regiment, with

soldiers recruited at the local level. He was assigned to the Infantry Regiment

Herzog Karl von Mecklenburg-Strelitz Nr. 43, 18th Company.

Although relatively late for action on the Eastern Front, William was sent to South Russia (Ukraine), probably resisting the last great Russian campaign of the war called the Brusilov Offensive. This campaign, designed by the Allies to draw German strength from the Western Front, began on June 4, 1916 and ended on September 20 of that year. He was captured near the end of this campaign, being taken prisoner by the Russians on September 16, 1916. He was one of 400,000 men taken prisoner by the Russians in this campaign. He suffered a head wound and was captured in Galicia between the Narajowka and the Zlota-Lipa rivers near Lemberg, now L'vov. He was sent east to Jekaterinoslaw (today Dnjepropetrovsk) where he worked in a salt mine.

There is no doubt that some prisoners of war fared considerably better than others. With limited information it is difficult to evaluate William's experience as a prisoner. However, a detail provided by his sister implies that things could have been worse for him. She said that not only did he have a girlfriend, but that the girlfriend was the daughter of the director of the salt mine. She reports that even though he was a prisoner of war, the fellowship was good, not just among the prisoners, but also with the Russians. Harold Olmstead writes the following in a 1971 exhibition catalog for the Charles Burchfield Center in Buffalo,

"'Bill' Ehrich came to this country from Germany after the First World War, most of which he passed pleasantly, so he told me, in a Russian prison camp doing heads of Russian officers!"

All of this came to an end with the Russian Revolution. William was released (luckily, as thousands of prisoners were not released until months and even years later). He was then sent to a German quarantine camp in Zegrze, Poland, north of Warsaw. It was now May 1918.

Even though the war in the east was over, fighting continued on the Western Front, where Muskateer Willy Ehrich was now sent. He served in France and Belgium before finally being released from the military in January 1919, having survived the war on both fronts.

The civilian population in wartime sustained great shortages. His sister Friedel describes their situation:

"It was really hard for the parents to feed the children. We were always hungry. Father got a piece of land where we planted potatoes and vegetables. In the shed we had one pig, two goats, six hens, six rabbits and a cat. Food was almost impossible to buy. In the field we grew some wheat for flour and so forth. It was really bad. It took years before it got better, 1923."

The post-war situation in East Prussia was in many ways more dire than in other parts of Germany or Europe. Located in the extreme northeast corner of the German empire and bordered by the Baltic Sea on its north, the Treaty of Versailles left it isolated, inflation skyrocketed, and daily life was harsh. It was the coldest area of Germany with the average temperature only 43 degrees F. Spring could not be said to begin until the second half of May, with late frosts occurring in June, making the growing season short.

East Prussia was sparsely populated compared to other parts of Germany. Much of this was due to steady emigration, often to the USA. The reasons for this exodus are undoubtedly the intense struggle for economic viability and, in some cases, unease with the developing political situation and the physical isolation from Germany itself by the Polish corridor. Between 1925 and 1934 an average of 15,000 people emigrated from East Prussia each year, leaving a country whose total population was approximately 2.2 million. It was flight from what we can see today as having been a far flung region of Eastern Europe. A region rich in history, culture, family, and tradition, but with very limited prospects for the future.

Through the Methodist church, William met a young lady named Ruth Herrmann who

lived with a foster family named Egler and their daughter Annie. After a long

courtship, they married in a civil ceremony in October, 1926, followed by a

church wedding at the Altstädtische Kirche at the end of the Paradeplatz. They

moved temporarily into an apartment at 11 Beydritter Weg, in the same building

as his parents.

Through the Methodist church, William met a young lady named Ruth Herrmann who

lived with a foster family named Egler and their daughter Annie. After a long

courtship, they married in a civil ceremony in October, 1926, followed by a

church wedding at the Altstädtische Kirche at the end of the Paradeplatz. They

moved temporarily into an apartment at 11 Beydritter Weg, in the same building

as his parents.

Financial survival for the young couple was problematic. Ruth worked in the office of a company that sold lighting fixtures, and William did contract work for the senior professors Schmidt-Kestner and Cauer, since without an established reputation, it was difficult to compete for the art funds that were scarce after the war. As a result, he failed to get proper credit for his work, such as the stone heads over the entrance to the Neue Burgschule and the reliefs over the entrance to the main train station. Given the career prospects and the hyperinflation that engulfed Germany, the couple began to consider other options.

In 1927, uncle Karl Ehrich of Buffalo, New York, who had immigrated earlier to

the US, came to Königsberg with Aunt Augusta to visit his brothers. William was

perceptive and open in his world view (in German, called

aufgeschlossenheit), and no doubt plans were made during that visit to

leave Germany. In 1928 William obtained his first US visa, but Ruth had

reservations, and so it was left to expire. In April, 1929, however, they

boarded the liner New York with all their furniture and headed for

Buffalo, New York, unaware of the world financial chaos to follow.

In 1927, uncle Karl Ehrich of Buffalo, New York, who had immigrated earlier to

the US, came to Königsberg with Aunt Augusta to visit his brothers. William was

perceptive and open in his world view (in German, called

aufgeschlossenheit), and no doubt plans were made during that visit to

leave Germany. In 1928 William obtained his first US visa, but Ruth had

reservations, and so it was left to expire. In April, 1929, however, they

boarded the liner New York with all their furniture and headed for

Buffalo, New York, unaware of the world financial chaos to follow.

The New World: Buffalo, NY

Although they could not possibly have known it at the time, Buffalo, NY, was probably one of the best cities in the country for William and Ruth Ehrich to establish a new life for themselves. It was home to thriving and well- established ethnic communities. Thousands of German Americans preceded them, providing access to neighborhoods, organizations and professional contacts. Family members were also there to welcome them warmly. In addition, due to such men as Seymour Knox, Gordon Washburn and others, the city had developed a keen appreciation for contemporary art.At the time of their arrival in Buffalo, William Ehrich was 32 years of age and his wife Ruth was five years younger. They had been married almost three years and were young, talented and ambitious. Nevertheless, the contrast with their previous life must have been daunting. Buffalo in 1930 was the 13th largest city in the US with a population of 573,076 and was a wealthy industrial behemoth. Königsberg, their previous home, had a population of only 311,000. They had to learn to speak English and become economically self-sufficient at the beginning of the world economic crisis.

The first home of William and Ruth Ehrich was with William's uncle Karl Ehrich and his wife Augusta, their sponsors in the New World. Karl and Augusta emigrated to the US in the last years of the 19th century, she in 1896 and he in 1899. They had two grown sons who also lived in Buffalo, the younger one, Karl, living at home. They owned their home at 14 Rey Street, near the intersection of Broadway and Jefferson. This dwelling was a small, frame home, of the type inhabited by thousands of blue collar workers in Buffalo.

Uncle Karl's occupation was "blacksmith" or mechanic for the Montana Cab Company, the largest taxi company in western NY. He worked there for many years and revered the Company president John C. Montana. At this time Augusta Ehrich did not work outside the home. William and Ruth would have been made welcome and would have found familiar the language, the food and the many common ties of family. But like all young people, they wanted to be economically independent and have their own home. So within a few months William found employment as a wood carver for the Kittinger furniture company. He and Ruth rented their first apartment in a multi-family home at 257 Lemon Street in the heart of Buffalo's "fruit belt" so named because the neighborhood was composed of several streets each bearing the name of a fruit. This was a dense, primarily German enclave. In April, 1930 the US census shows them living on Lemon Street, paying a monthly rent of $22.

Several other moves followed for William and Ruth - to 85 Fox Street in 1931 and to 43 Harriet Avenue in 1936. While such moves are not unusual, there must have been compelling reasons since they had brought with them from Königsberg an extensive collection of heavy furniture that included oak beds, wardrobe, marble-topped table, a 7-foot tall grandfather clock, and an enormous marble-topped buffet, all of which stayed in the family throughout the moves until 1986. In the meantime, Buffalo's industrial vitality has largely vanished, and the population in 2009 was less than half what it was in 1930. The Lemon Street house has been demolished and in 2009 the Fox Street house is a boarded up derelict in a decaying neighborhood.

Survival in the early years of the Depression was difficult for everybody, but

much more so for a German-speaking immigrant sculptor. However, it's remarkable

that a stranger to the city was able to arrive in 1929 and in a relatively short

period of time become one of its leading artists. In 1929 learning English in

night school classes was an important first step. Ruth related that in the first

years she scrubbed floors for 25¢ a day and was too poor to take a bus home. At

night she would cry herself to sleep over the loss of the relative comfort of

their former home in Germany. They made friends, however - including the

Ilsankers whom they met on Lemon Street, the Schaafs, the Heinings who lived on

Harriet Avenue, and of course, Karl and Augusta Ehrich and their family, whom

they called just Onkel und Tante.

Survival in the early years of the Depression was difficult for everybody, but

much more so for a German-speaking immigrant sculptor. However, it's remarkable

that a stranger to the city was able to arrive in 1929 and in a relatively short

period of time become one of its leading artists. In 1929 learning English in

night school classes was an important first step. Ruth related that in the first

years she scrubbed floors for 25¢ a day and was too poor to take a bus home. At

night she would cry herself to sleep over the loss of the relative comfort of

their former home in Germany. They made friends, however - including the

Ilsankers whom they met on Lemon Street, the Schaafs, the Heinings who lived on

Harriet Avenue, and of course, Karl and Augusta Ehrich and their family, whom

they called just Onkel und Tante.

In an article written in 1946, William reflected back on his career hopes when he arrived in Buffalo, "When I came to America in 1929, I did not find the architectural employment I was hoping for..." His high hopes had to be modified considerably.

William eventually lost his carving job at Kittinger, apparently because he was too meticulous about his work and didn't have the productivity they wanted. At first he continued to carve the large Barlach-style wooden sculptures he had carved in Germany, but times were difficult and the market did not support the sale of such large pieces. Eventually he met a gift shop owner named Pitt Petri who convinced him that smaller articles would be easier to sell. William created a set of small animals including a duck, penguin, cat, bear, rooster, and deer with fawn. From these prototypes he made plaster molds that he used to mass produce delicate clay copies, most of which were finished with a bright white glaze. He sold these china animals by the hundreds. Also, in the mid-'30s, William produced hundreds of pencil and charcoal sketches. However, most of these were unflattering sketches of nudes. Judging from the number of these still in existence, they didn't have the market appeal of the animals.

In 1933 another opportunity opened for William. He received an appointment as an instructor at the Art Institute of Buffalo (AIB), a well-known western New York art school. This school existed from 1931 to 1956, and its archives are now located at the Burchfield Penny Art Center in Buffalo. William had immediate success as a teacher and established a reputation that would follow him throughout his career. The AIB was supported in part by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) through the Federal Art Project (FAP) that was created by the federal government in August, 1935, to assist artists with no other means of support. William's popularity at the AIB attracted the attention of the supervisors of the FAP in New York, and in May, 1938, he was appointed supervisor of the Buffalo Unit of the Federal Art Project. His departure from the AIB that May was accompanied by pages of accolades from his students, including the following:

|

There's cherry-wood chips in our hair, Our fingers are covered with clay; Fifty-six Starin seems bare Because you are going away. |

We know that reports of your fame Will ever continue to reach us, But the Institute won't be the same Without Mr. Ehrich to teach us. |

and

|

To fit the hand whose magic is supreme In giving life to stone, and wood, and clay, This token of affectionate esteem We offer as a parting gift today. |

We've had good times with clay and wood and plaster; Without your help our daydreams wouldn't grow... And now in heartfelt tribute to the Master: We Hate Like Everything to See You Go!! |

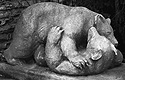

The focus of William's work on the FAP was the Buffalo Zoo, which saw

significant expansion with WPA assistance from 1938 through 1942.

William supervised a cadre of sculptors and painters who created murals in the

reptile house, sgraffito on the animal house exterior, and the concrete animals

at the zoo entrances that are still there today. Unfortunately none of the

records of the Buffalo Zoo or the National Archives document which works are

specifically his, but his notes suggest that he created the animal figures on a

fountain, the sgraffito, and some of the animals at the zoo entrances.

The focus of William's work on the FAP was the Buffalo Zoo, which saw

significant expansion with WPA assistance from 1938 through 1942.

William supervised a cadre of sculptors and painters who created murals in the

reptile house, sgraffito on the animal house exterior, and the concrete animals

at the zoo entrances that are still there today. Unfortunately none of the

records of the Buffalo Zoo or the National Archives document which works are

specifically his, but his notes suggest that he created the animal figures on a

fountain, the sgraffito, and some of the animals at the zoo entrances.

By 1936, William attracted the attention of the Memorial Art Gallery (MAG) in

Rochester, New York, when he taught a 1-day class there. This engagement led to

an appointment from the director, Gertrude Moore, as instructor in the fall of

1937. At the MAG he taught 6 classes a week, on Wednesdays and Thursdays, for an

annual salary of $1,500. Objections were raised by the government about the

permissibility of simultaneous appointments at the FAP and the MAG, but it was

ruled that the exclusivity provisions of the FAP applied only to the FAP workers

and not to the project directors. Nevertheless, William resigned his FAP

position in 1939 to focus on what was to become a major new phase of his

profession. Commuting to Rochester necessitated accessible transportation, so in

May, 1937, William and Ruth bought their first car, a 1936 Oldsmobile, that was

to serve them several years.

By 1936, William attracted the attention of the Memorial Art Gallery (MAG) in

Rochester, New York, when he taught a 1-day class there. This engagement led to

an appointment from the director, Gertrude Moore, as instructor in the fall of

1937. At the MAG he taught 6 classes a week, on Wednesdays and Thursdays, for an

annual salary of $1,500. Objections were raised by the government about the

permissibility of simultaneous appointments at the FAP and the MAG, but it was

ruled that the exclusivity provisions of the FAP applied only to the FAP workers

and not to the project directors. Nevertheless, William resigned his FAP

position in 1939 to focus on what was to become a major new phase of his

profession. Commuting to Rochester necessitated accessible transportation, so in

May, 1937, William and Ruth bought their first car, a 1936 Oldsmobile, that was

to serve them several years.

William left in Buffalo a legacy of artistic work that included numerous works in private collections and a number of public commissions, including a bronze tablet in honor of Buffalo mayor Charles Roesch located in the foyer of City Hall, the statue of St. Andrew at St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, and a head of Pitt Petri's son Peter, likely done in partial compensation for Pitt's generous help and advice in those early years.

The Productive Years: Rochester, NY

The Memorial Art Gallery was housed on the site of the College for Women at the University of Rochester's Prince Street Campus, which was a considerable distance from the University's River Campus. Beginning in 1941 William's studio and classroom were located in Carnegie Hall, a women's dormitory, on that campus. In 1939, Carl Hersey, chair of the Department of Art History, also offered William an additional $500 to teach a sculpture class for the University at the MAG. These dual appointments continued for the rest of William's career. In 1955 the College for Women merged with the men's college at the River Campus and much of the Prince Street Campus was sold. William's studio and sculpture classrooms were then moved to specially built quarters in Fauver Stadium.

After leaving the Federal Art Project, William had only minor teaching

responsibilities in Niagara Falls, and there was even less reason to remain in

Buffalo. In 1941 he purchased a small home at 49 Klink Road in Rochester with

the help of a $5,000 mortgage financed by Pitt Petri and his wife, Elisabeth.

This house had been built by the Brumfield family and was in relatively

primitive condition, although the owners had made considerable efforts to

landscape the property. The long gravel driveway was an eyesore, however, so

William and Ruth ordered sacks of concrete and paved it themselves, one sack

after the other. Thereafter they put great effort into the surrounding gardens

and interior renovations. William took great pride in the gardens that occupied

the rear two-thirds of the 280-foot lot. The middle third contained trees and

flower beds, fireplace, sculptures, and a fountain in the center. The remaining

third was a vegetable garden that contained every imaginable fruit tree as well

as prolific raspberry, currant, and gooseberry bushes. During the '40s much of

the produce was canned or frozen for use during the winter.

After leaving the Federal Art Project, William had only minor teaching

responsibilities in Niagara Falls, and there was even less reason to remain in

Buffalo. In 1941 he purchased a small home at 49 Klink Road in Rochester with

the help of a $5,000 mortgage financed by Pitt Petri and his wife, Elisabeth.

This house had been built by the Brumfield family and was in relatively

primitive condition, although the owners had made considerable efforts to

landscape the property. The long gravel driveway was an eyesore, however, so

William and Ruth ordered sacks of concrete and paved it themselves, one sack

after the other. Thereafter they put great effort into the surrounding gardens

and interior renovations. William took great pride in the gardens that occupied

the rear two-thirds of the 280-foot lot. The middle third contained trees and

flower beds, fireplace, sculptures, and a fountain in the center. The remaining

third was a vegetable garden that contained every imaginable fruit tree as well

as prolific raspberry, currant, and gooseberry bushes. During the '40s much of

the produce was canned or frozen for use during the winter.

The early '40s were war years during which everyone suffered from shortages and tight money. This was severe enough for William and Ruth that there were times when William considered leaving the University for the commercial world in order to survive. Economic struggles caused tensions between him and the University, and he made some attempts to seek additional employment at schools such as the Columbia School. In 1943 things became yet more complicated with the arrival of son Roger. William and Ruth were always positive, never discussing what they lacked, and their son was unaware that not all his winter coats came from stores.

William was continuously active and frequently at work six days a week. Weeknights he often taught adult classes at the Memorial Art Gallery. On those days, when he arrived home following a day at his studio, he would scan the newspapers (at that time the Times Union and the Rochester Abendpost, a German language paper written in the old German script called Frakturschrift), take a short nap after dinner, and then return to work teaching evening classes. No accurate count of the number of art pieces he created in Rochester is available because the remaining lists include duplications, but there were probably at least a thousand. The larger works done on commission would require extensive correspondence with clients and the suppliers of materials and services, as well as a substantial amount of bookkeeping. In addition to teaching, William participated in frequent exhibitions. These involved marketing, shipping, and travel, which were a further time burden. Although both William and Ruth spoke and wrote excellent English, most of the management and correspondence was left to Ruth, who typed letter after letter on the old 1936 Woodstock typewriter in the bedroom. This was a time long before computers, and even long distance telephone calls were financially out of reach.

Following WWII William made a concerted effort to help his family survive in Germany. He and Ruth packed 220 20kg packages of cloth, lard, and coffee, and there was always a partially filled box in the kitchen in which the next shipment accumulated.

William was a gregarious member of numerous social groups in Rochester, which included his students, professional art patrons such as the Sibleys and the Watsons, German organizations such as the Kulturelle Gesellschaft (Cultural Society), artists, and personal friends. One of his closest friends was Ewald Appelt, a professor of German literature in the German department of the University. They would spend hours discussing Goethe and Schiller and undoubtedly University politics. Appelt's death in 1954 was a considerable loss, and William made a special ceramic funeral urn for his friend.

In the early years, the family joined the St. Paul German-Lutheran church where Pastor Schreiber still held German services, and organist Macklin was the magnificent master of the pipe organ that supported the Lutheran liturgy. Eventually the church changed, and the family visited church after church, looking for a dynamic pastor with the intellect to place current social and religious issues into a broader historical context. Eventually they found Pastor Antonio Marino of Brighton Presbyterian Church, who served them from that time on.

In 1951 William forged a close friendship with a prolific Lithuanian painter, Alfonsas Dargis, who immigrated to Rochester from Germany that year as a displaced person. William helped Dargis make professional connections in Rochester that enabled him to sell 1,500 paintings between his arrival and when he returned to Germany in 1985. Since Dargis spoke little English and had no car, joint excursions in western New York were frequent, and there were many parties that lasted into the early morning hours. Other friends included the families of weaver Elsie Frielinghaus, painter Paul Heiner, instrument maker Paul John, embryologist Johannes Holtfreter, realtor Helen Mittmann, and, of course, the family of his cousin, Lud Ehrich, a Kodak executive who lived in Rochester.

William did not work all the time, however; there would always be a 1-week vacation in the summer. The Adirondacks of northern New York, the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and southeastern Canada were frequent vacation goals, and occasionally a week would be spent in a cabin at Allegheny State Park south of Buffalo. William's friends, the Fenns, often invited the family to spend a week at a cottage on their property on nearby Canandaigua Lake.

William smoked cigarettes most of his life, and when angina symptoms developed in the early 50s, his cardiologist implored him to give up smoking. He tried desperately to do this by smoking half cigarettes with a filter holder, but was unable to give it up completely. One afternoon at the Memorial Art Gallery he suffered a heart attack but swore those who came to his aid to silence, which his family learned only after his death years later. That evening he ate little dinner, took a nap, and left as usual for his evening class at the art gallery.

In 1955 William and his family returned to Europe for a reunion with brothers Walter and Kurt and sisters Friedel and Lotte, all of whom had settled in the Rhineland after their escape from East Prussia. Travelling on the ship Homeric from Montreal, they took along their 1952 Plymouth Plaza, which provided reliable transportation during their 3-month visit. Since William had never seen central Europe before, they traveled for a month with Friedel and lawyer husband Siegfried who helped with logistics and with the language while in France. William, of course, was overwhelmed by the art and seemed determined to visit every cathedral and art museum in France and Italy. Europe at the time was still recovering from the war, and parts of the major cities were still in ruin. The roads, too, were narrow and winding and provided an exciting challenge on the mountain passes for the Plymouth, which the family respectfully called the Straßenkreuzer or street cruiser.

Back in Rochester, the move to new quarters on the River Campus and a promotion stimulated a burst of creative activity. Since space was now available, William decided to create his own bronze foundry, and to do that, received a study grant in summer 1959 to learn bronze casting techniques with Heinrich Kirchner in Munich. Upon his return to the University of Rochester in the fall, the foundry came into existence quickly and was very successful, although the work would end suddenly with his death a year later.

Professional Career

William lived and studied at the height of the German expressionist era and was a contemporary of many of the well-known artists of the time such as Käthe Kollwitz, Ernst Barlach, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, and Georg Kolbe. Königsberg with its two art schools was a center of expressionist sculpture, but sadly both art schools and a significant number of the works they produced were annihilated during World War II (see for example, Mühlpfordt, 1970). William never abandoned his expressionist roots, but later in his career he became more interested in form and the emotional appeal of shape, feel, and texture.William was known throughout his career for his ability to work in diverse media including wood, stone, clay, plaster, charcoal, enamel, and various metals such as bronze, copper, and lead. Given the raw material, he would visualize the end result, sometimes drawing on the wood or stone with his black marker. He would never make preliminary sketches unless one was needed by a client. He had an innate ability to match his concepts to the medium, making his work grow naturally out of the material. In his own words,

"Sculpture, a three-dimensional art expression, has an advantage over sound, color, and movement, that it can be enjoyed forever by the sense of touch, too. Stone, wood, and clay permit my hands to caress my work - as I expect others to enjoy it too by physical contact. My aim is to render my formalized message as concisely as possible. My respect for the media employed often leads me to utilize a suggested, formal shape of stone and wood as I find it."

Often on Sunday outings to the Lake Ontario beaches he would scan the fieldstones on the beach, looking for those with potential for carving. When he found interesting stones, he would sketch his ideas directly on the stones with his marker. The promising stones would then be mounted on a large limestone block using plaster and carved with hand chisels and usually an air hammer. Among the better known pieces were his owls, most of which are in private collections. Four of the larger fieldstones, #8-Broodess, #27-Half Figure, #38-Little Cloud, and #120-Contemplation, are distinguished in that the figures have a highly polished front surface and seem to emerge from large raw brown stones. Little Cloud is among those in the permanent collection of the Memorial Art Gallery in Rochester.

William acquired an unusual skill for lettering as a young artist in Königsberg and used this skill to make commemorative tablets that were usually cast in bronze. Once the shape of the desired tablet was known, he would pour a plaster blank that would be carved to produce a negative image of the final tablet. The blank would be carved with wood chisels in a negative mirror image of the desired inscription while keeping the type font and size absolutely uniform across the entire tablet. The carved blank was then coated with soap, and a positive copy of the final tablet was made by another pour of plaster. Due to the soap film on the negative original, the positive would be lifted from the negative and then sent to the bronze foundries after the repair of minor defects such as bubbles. Most of these tablets were cast either by the Roman Bronze Works on Long Island or by Gorham in Providence.

A substantial number of bronze tablets were produced, including four for the Tannenberg National Monument in East Prussia, several in Buffalo, including one in honor of Mayor Roesch located in the foyer of City Hall, and a large number in Rochester, especially at the University. In addition, William was often asked to produce award medallions using the same production process. Among the major tablets in the US are those for:

- Charles Roesch, Buffalo, 1937

- Kate Gleason, East Rochester, 1949

- Henry Alvah Strong, George Eastman House, Rochester, 1952

- Chester Whitin Lasalle, Whitinville, MA, 1954

- Frank W. Lovejoy, University of Rochester, 1955

- Earl B. Taylor, University of Rochester, 1956

- Charles Hoeing, University of Rochester

- Frank Gannett (in wood), Ithaca, NY, 1957

- Donald W. Gilbert, University of Rochester, 1960

- Bellman's Society, University of Rochester

William was exceptionally well known in Western New York, where hundreds of his works are in private collections. He had numerous one-man shows of his works, including those at

- Albright Gallery (Buffalo)

- Clay Club, now the Sculpture Center (New York City)

- Cornell University (Ithaca)

- Memorial Art Gallery (Rochester)

- Rundel Gallery (Rochester)

- Woodside Gallery (Rochester)

and participated in numerous other exhibitions including those at

- Albright-Knox Gallery (Buffalo)

- Arena Group (Rochester)

- Buffalo Society of Artists (Buffalo)

- Memorial Art Gallery (Rochester)

- Metropolitan Museum (New York City)

- Museum of Contemporary Crafts (New York City)

- National Ceramics Show (Syracuse)

- Nelson Rockwell Gallery (Kansas City)

- Riverside Museum (New York City)

- Rundel Gallery (Rochester)

- Rush-Rhees Gallery (Rochester)

- Sisti Gallery (Buffalo)

William rarely exhibited his works without winning awards, although the records are too sparse to identify all of them. At the Albright-Knox Gallery, he won the Patteran Prize in 1938 and won prizes at 12 of the 22 annual Western New York Exhibitions that took place there up to 1956. The Albright gallery acquired his sculpture, #85-Destiny, in 1940. At the Memorial Art Gallery in Rochester he exhibited in most Finger Lakes Exhibitions and won awards at 9 of them. These included the Lillian Fairchild Memorial Award in 1942 and the Juror's Show Award in 1949. The specific awards were:

- Prophet, 1st prize in sculpture (1940)

- Assyrian, Purchase Prize (1942)

- Thrown Cookie Jar, 2nd prize in ceramics and Night, 2nd prize in sculpture (1947)

- Group of 3 Sculptures, 2nd prize in sculpture and Decorated Plate, 1st prize in ceramics (1948)

- The Provider, most expressive use of a sculptural material (1949)

- Embrace, 1st prize, H.H. Sullivan Award and Plate with Figure, 3rd prize in ceramics (1950)

- Reclining Nude, Stella Garson Memorial Prize for Sculpture (1952)

- Cloud and Prodigal Son, H.H. Sullivan Award (1953)

- Symmetrical Abstraction of a Figure, H.H. Sullivan Award (1957)

In addition to his regular activities at the University and at the Memorial Art

Gallery, William took on other large projects in Western New York. He created a

number of portrait heads, a pair of 6-foot redwood eagles for the Union Trust

Company in Rochester (1952), a bronze garden fountain for Hildegard Watson

(1953), and the Eternal Flame at the Rochester War Memorial (1955). Bronze

fountain figures were commissioned of Alice Merckens (of Merckens Chocolates)

in Buffalo in 1949, and of Connie Stafford in Buffalo in 1953. Another major

project was a set of seven 3-foot fish enameled on ¼" copper stock, fabricated

in the ovens of the Pfaudler Company in Rochester. These were commissioned in

1953 by White Haven Cemetery in East Rochester and reflected William's strong

religious concept of eternal life. The fish were positioned to leap among the

sprays of a large fountain near the cemetery entrance. To his surprise, the fish

were removed when cemetery clients, apparently missing the symbolism, complained

that the playful splashing of the fish was inconsistent with the somber context

of the cemetery.

In addition to his regular activities at the University and at the Memorial Art

Gallery, William took on other large projects in Western New York. He created a

number of portrait heads, a pair of 6-foot redwood eagles for the Union Trust

Company in Rochester (1952), a bronze garden fountain for Hildegard Watson

(1953), and the Eternal Flame at the Rochester War Memorial (1955). Bronze

fountain figures were commissioned of Alice Merckens (of Merckens Chocolates)

in Buffalo in 1949, and of Connie Stafford in Buffalo in 1953. Another major

project was a set of seven 3-foot fish enameled on ¼" copper stock, fabricated

in the ovens of the Pfaudler Company in Rochester. These were commissioned in

1953 by White Haven Cemetery in East Rochester and reflected William's strong

religious concept of eternal life. The fish were positioned to leap among the

sprays of a large fountain near the cemetery entrance. To his surprise, the fish

were removed when cemetery clients, apparently missing the symbolism, complained

that the playful splashing of the fish was inconsistent with the somber context

of the cemetery.

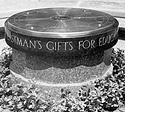

William created three other major art works for the University of Rochester. In

1952 the graduating class contributed a bronze sundial which was somewhat

optimistically mounted on a set of boulders between the men's residence halls

and fraternity quad. The gnomon was broken off almost immediately, and the

sundial was anointed by the students with numerous coats of paint. Within a few

years the sundial had disappeared completely. In 1955, William was commissioned

to create a large enameled dandelion, the official flower of the University.

Originally designated for the façade of the new women's residence hall, its 5

foot diameter was not sufficiently visible, and it was moved to the façade of

the men's gym, now the Goergen Athletic Center, where it looks down on Dandelion

Square. The dandelion is constructed of individual petals hammered from sheet

copper and mounted on a stainless steel shell. The enameling was subcontracted

to William's son Roger for a dollar a petal. The most visible work at the

University is the engraved stainless steel Meridian Marker, known as the Eastman Centennial Monument, which is located in the

center of Eastman Quadrangle. The monument was donated in 1954 by Charles Force

Hutchinson, a friend of George Eastman, in observance of the centennial of

George Eastman's birth.

William created three other major art works for the University of Rochester. In

1952 the graduating class contributed a bronze sundial which was somewhat

optimistically mounted on a set of boulders between the men's residence halls

and fraternity quad. The gnomon was broken off almost immediately, and the

sundial was anointed by the students with numerous coats of paint. Within a few

years the sundial had disappeared completely. In 1955, William was commissioned

to create a large enameled dandelion, the official flower of the University.

Originally designated for the façade of the new women's residence hall, its 5

foot diameter was not sufficiently visible, and it was moved to the façade of

the men's gym, now the Goergen Athletic Center, where it looks down on Dandelion

Square. The dandelion is constructed of individual petals hammered from sheet

copper and mounted on a stainless steel shell. The enameling was subcontracted

to William's son Roger for a dollar a petal. The most visible work at the

University is the engraved stainless steel Meridian Marker, known as the Eastman Centennial Monument, which is located in the

center of Eastman Quadrangle. The monument was donated in 1954 by Charles Force

Hutchinson, a friend of George Eastman, in observance of the centennial of

George Eastman's birth.

The

200th anniversary of the poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, in 1949 led to

another major project. A monument was created for Highland Park in Rochester

after a committee, chaired by Ewald P. Appelt, raised the required funds.

William was chosen to construct this monument. The original $10,000 design

included a central shaft bearing a bronze bust of Goethe and two side panels

bearing selections of his poetry. When describing this project, William

wrote,

The

200th anniversary of the poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, in 1949 led to

another major project. A monument was created for Highland Park in Rochester

after a committee, chaired by Ewald P. Appelt, raised the required funds.

William was chosen to construct this monument. The original $10,000 design

included a central shaft bearing a bronze bust of Goethe and two side panels

bearing selections of his poetry. When describing this project, William

wrote,

"For the portrayal of Goethe's personality, I considered no particular phase of his life. His spiritual aristocracy appears to me to be the point requiring stress, culminating in his immortal appearance around the age of sixty-five."

The required funds did not materialize, and there was disagreement with the city about the location, requiring a major redesign and elimination of the side panels. However, the revised project was completed, and the Goethe monument stood on a rise above the concert shell in Highland Park from September 17, 1950 until its theft in July, 2015.

Following the theft, a small group formed to fund, site, and restore the lost monument. Work began in June, 2021 and culminated with the unveiling on May 5, 2023 of a reproduction of the bronze at the same scale as the original. The monument is now located in the Rundel Memorial Library in downtown Rochester.

Family Endpiece

On May 1, 1938 William's parents came to Buffalo to visit for several months, after which they said goodbye forever. They died of natural causes before the destruction of Königsberg and were spared a gruesome death. As of 2009 most of the buildings on their street on the northern perimeter of Königsberg still stand, although their own apartment building is gone.Sister Charlotte and her husband left Königsberg after WWI and operated a home for the elderly in Remscheid, Germany into their old age. Sister Helene and her children made it to a resettlement camp in Denmark where she died of disease. Sister Friedel was a pediatric nurse in Berlin during WWII, and she fled to Barby near Magedeburg before the Russians reached Berlin at the end of the war. Her husband, Siegfried Middelhaufe, refused to join the National Socialists and was imprisoned in Insterburg. After the war, being a lawyer, he was recruited to help form the new German police force in Düsseldorf, where they had a beautiful apartment on Kaiser-Friedrich Ring in Oberkassel, overlooking the Rhine. Brother Kurt's family was on the last train out of Königsberg before the city was sealed, but it's not known how he himself escaped to the west. Brother Walter was in the military; his family fled to Klein Rade (Radówek), Poland, near Frankfurt/Oder in 1944 after the firebombing, leaving behind the home they had built on Hoverbeckstraße and all their belongings. After 5 months they were driven to Zielenzig (Sulecin), east of Klein Rade, where their 2-year-old daughter Rosie died of measles. From there they fled back to Klein Rade, then to Barby, and eventually to Remscheid where they made their final home. Besides Kurt and Walter, Walter's three sons, Horst, Klaus, and Hans, also became architects, as did Klaus' daughter, Sabine.

William lost all contact with his brothers and sisters during WWII, just as they lost contact with one another. After the war with the help of the Red Cross and through good fortune, they reestablished contact with one another and with William, learning for the first time that a son had arrived on the other side of the Atlantic. No pre-war photos or documents survive, other than those that William and Ruth brought with them to the US in 1929 and those mailed to them before the war.

Ruth Ehrich died in Rochester, New York, in 1992 after a long illness. Son Roger is now Professor Emeritus of Computer Science at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Virginia, where his wife, Marion, is Professor Emeritus of Veterinary Medicine

Königsberg was firebombed by the British in August, 1944. After 6 weeks of shelling by the Soviet army, it capitulated on April 12, 1945 (Lasch, 1977). The city interior was almost entirely destroyed, ending a 700 year old civilization founded in 1255 by the Teutonic Knights. Samland was ceded to Russia August 2, 1945, at Potsdam, and the city was renamed Kaliningrad on July 4, 1946. During the cold war Kaliningrad was sealed from the West. As a result, neither William nor Ruth ever returned to their homeland, and they never learned what we now know about the horror and destruction during its last days.

Papers and photos are archived in the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. Remaining art works including sculptures, ceramics, and sketches are being added to the collection of the Burchfield Penny Art Center in Buffalo, New York. A brief testimonial was written by John R. Slater, Professor of English, University of Rochester.

RWE, 2011

Link to Genealogy

References, in Chronological Order

- Sculptor Airs Art Views As He Starts Duties Here, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 4, 1938, p. 19.

- Menadue, Virginia Ford, Universal Quality About Work of Artist as Well as Himself, Buffalo Courier Express, May 4, 1941.

- Artists Let Down Their Hair, Buffalo Courier Express, p. 2 of Buffalo Courier Express Pictorial, June 8, 1941.

- The Carved Sculpture of William Ehrich, American Artist 10 (4), April 1946, pp. 21-24.

- Suhr, Elmer G., Rochester's Goethe Monument, Source Unknown, September 17, 1950.

- William Ehrich, The American-German Review 17 (4), Philadelphia: Carl Schurz Memorial Foundation, Inc., April 1951, p. 10.

- Slater, John R., The Eastman Centennial Monument, University File on the Meridian Marker - Eastman Quadrangle - River Campus, in the University Archives, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Rush Rhees Library, July 12, 1954.

- Slater, John R., William Ehrich, a Modest, Reverent Artist, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 12, 1960, p. 16.

- Tarrant, Pete, Plans for Merged Campuses, Teaching, Busy UR Sculptor, The Campus, University of Rochester, November 19, 1954, p. 2.

- Prof. Ehrich's Art Displayed in Gallery; Wood, Stone Sculpture, Drawings Shown, Campus Times, University of Rochester, September 27, 1957.

- Smith, Virginia Jeffrey, UR Artist Expert In Several Mediums, Rochester Times Union, September 30, 1957, p. 18.

- Mühlpfordt, Herbert M., Königsberger Skulpturen und ihre Meister 1255-1945, Holzner Verlag, Würzburg 1970.

- Lasch, Otto, So Fiel Königsberg, Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart, 1977.